I once sat on a jury in a minor criminal trial. The trial itself was unremarkable, but I’ll never forget two elements of the judge’s instructions to the jury. The first was his point that “reasonable

doubt” means what it says: It isn’t enough for a juror to assert a vague doubt or a hunch; there has to be a reason for it. The second was his advice about how to weigh conflicting testimony: There are no special criteria that apply only in court. To decide who is lying and who is telling the truth, the juror uses the same human radar that he or she has developed to navigate everyday life.

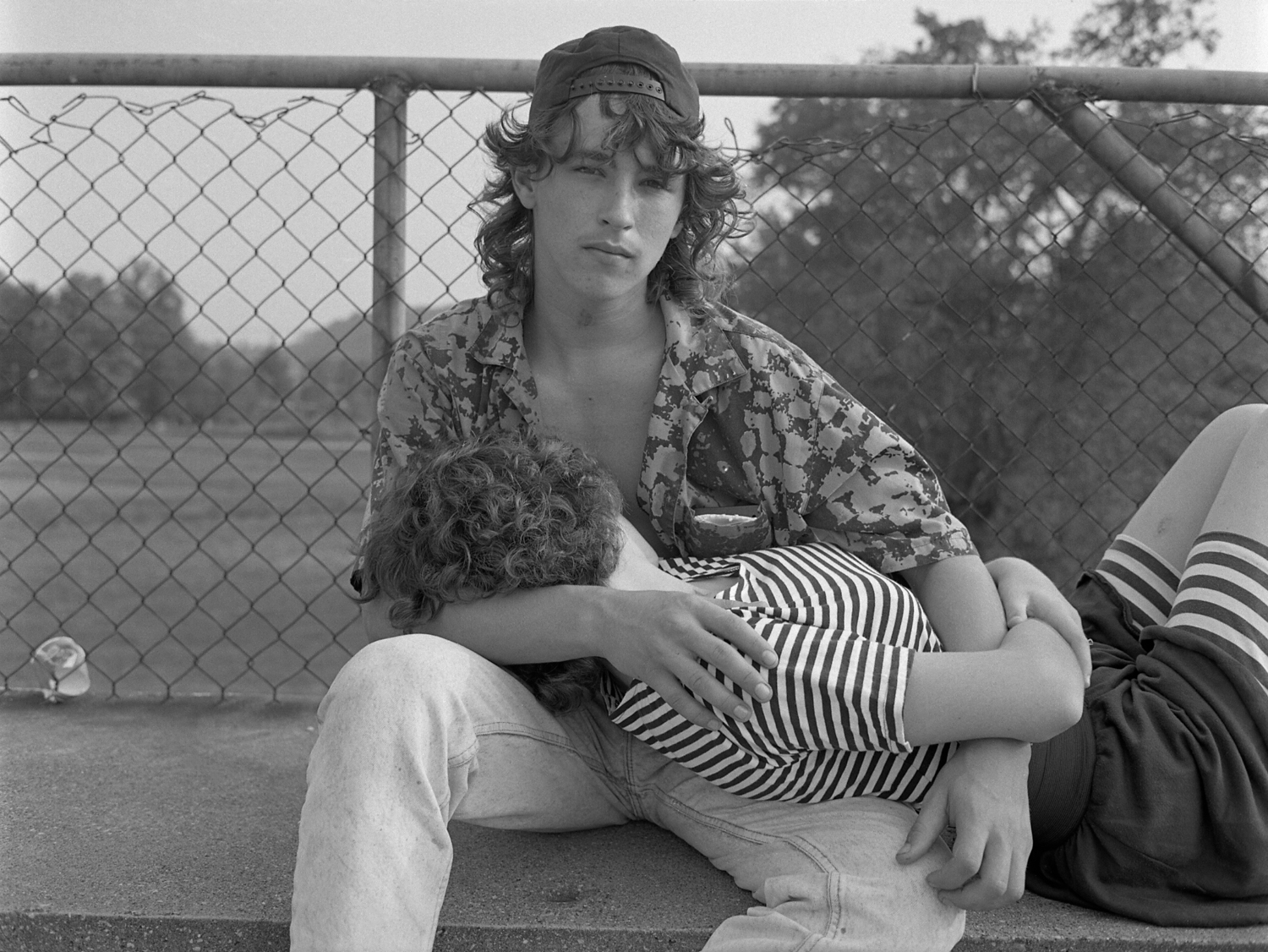

There are no special criteria for photography either. Photographs in general, especially photographs of people, and above all photographs of individuals propose a relationship between the viewer and the subject. Looking at the picture, we assess the character of that relationship. Is it spontaneous or calculated, frank or sly, superficial or probing, generous or mean-spirited, fascinating or boring? Is it honest or dishonest?

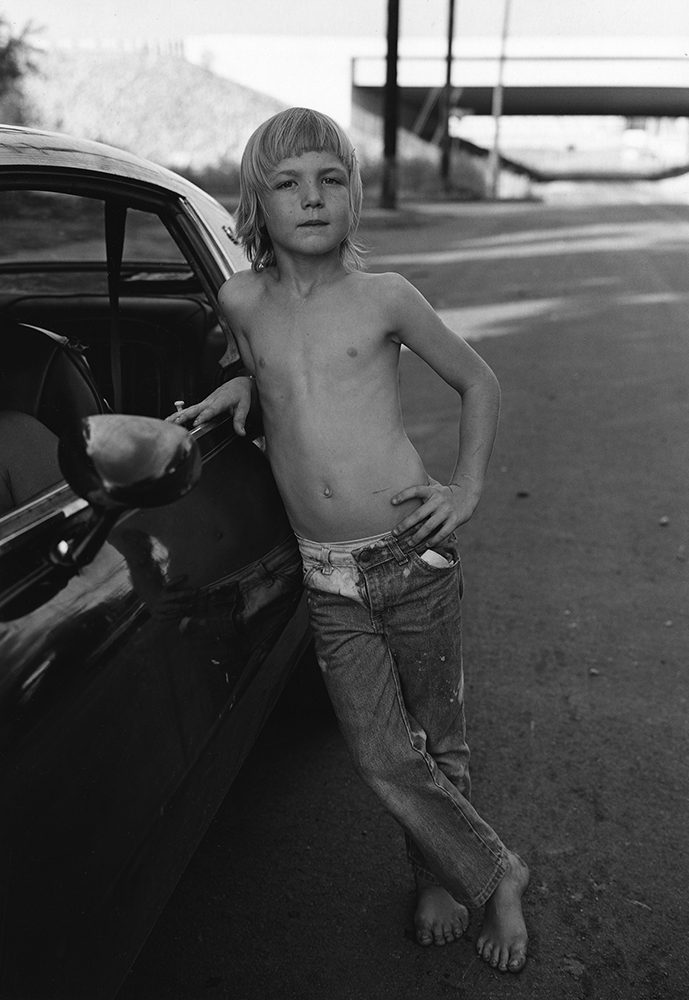

Mark Steinmetz works in a venerable tradition of photographic prowling that bets everything on the ordinary. Each picture is the fruit of an unplanned encounter: Though the photographer may know more or less where he is going, he can’t know precisely what he will find. An accumulation of these improvised perceptions can make both a world and a way of looking at it.

Superior craft need not play a role in this achievement, but in Steinmetz’s case it does. The precision with which his pictures render a wisp of hair, or a wrinkle of cloth, or the golden light (in black-and-white!) is at once a vehicle of careful observation and a metaphor for patient attention. It lends an aura of delicacy to the scenes without figures, of which there are quite a few for a photographer who is so frankly devoted to people. It’s tempting to say that Steinmetz’s places have personalities.

The socio-economic parameters of the world Steinmetz has chosen to explore are obvious enough, and he neither stresses nor avoids them. What he is after is much more personal or, perhaps it is better to say, much more individual (for there is no reason to believe that the photographer has ever met any of his subjects or will ever see them again). Indeed the hallmark of Steinmetz’s work—the quality that makes us trust his testimony—may be the unblinking constancy with which his photographs solicit grave interest in particular people without claiming unearned intimacy or insight.

Peter Galassi, Chief Curator of Photography at the MoMA from 1991 to 2011.

Extract from South East, Nazraeli Press